The Devil returns… Screen still from RGHC-0055.

In the film’s final act, the Devil descends into a narrow box canyon, his face obscured by a hooded cape. After Liah’s abduction, he appears only at the margins of the frame—less a figure than a pressure within the landscape. Liah alone sees him, his presence disturbing the guilty and terrified outlaws. Here, at the center of a labyrinthine terrain, the Devil reunites with Liah, revealed as Jeroboam—her murdered counterpart—returned through the completion of her final act of revenge.

Orville Wanzer & The Devil’s Mistress: A New Mexican Acid Western

A Photographic Essay“All invention and creation consist primarily of a new relationship between known parts.”

This photographic essay accompanies Birth of the Acid Western and offers an early look at The Devil’s Mistress (1965)—a regional, independent film made in Las Cruces, New Mexico, years before the Acid Western had a name.

What follows is not a comprehensive history, but a guided sequence of stills and reflections tracing how one outsider film anticipated a genre that would fully emerge in the late 1960s and early 1970s: the Acid Western.

Archival Film Elements (Color Trims & Outtakes)

RGHC-0055, Rio Grande Historical Collections

These images derive from RGHC-0055, a loose-reels collection of trims and outtakes from Bruja (later titled The Devil’s Mistress). Preserved in better condition than circulating prints, these elements retain the film’s original color palette and surface texture. They offer rare insight into Wanzer’s compositional precision and form part of the larger preservation effort central to Birth of the Acid Western.

Orville “Bud” Wanzer. Associated Press publicity photograph , (1964).

Produced for The Devil’s Mistress , this image situates Wanzer publicly as both filmmaker and intellectual advocate for cinema as a serious art form during his tenure at New Mexico State University.

Orville Wanzer: Outsider Formation

“There are two types of films. One is superficial entertainment, which packs the drive-ins. The other is the serious film. Nobody discusses a Presley film afterward, but you can’t keep people quiet about a Bergman film.”

Orville Wanzer was a visionary outsider in American cinema. Born in Queens in 1930 and raised in Brooklyn, he described himself as “movie-made”—formed as much by early immersion in cinema as by urban grit. His interests moved fluidly across film, literature, authorship, and radical art practices.

After working as a projectionist in the Navy and experiencing a brief, unfulfilling encounter with Hollywood—described in contemporary press as a detour rather than a destination—Wanzer pursued a master’s degree in English at Miami University. There he met Joan, who would later play the lead in his script Bruja.

When the couple relocated to Las Cruces, New Mexico, Wanzer was struck by the dramatic peaks of the Organ Mountains and imagined them as a film setting. Far from the centers of cinematic power, he began cultivating cinema as something to be studied and made locally—outside the studio system, with an amateur cast—combining the immediacy of Italian cinema with the taboo sensationalism of American B-movies.

WGW Productions on set. Associated Press production still for The Devil’s Mistress, (1965).

Pictured from left to right: Forest Wesmoreland (actor and key collaborator), Teddy Gregory operating the 16mm Bolex camera, and Orville Wanzer at lower right. Framed in the foreground is Doug Warren (Joe), a local musician and actor who also contributed to the film’s soundtrack alongside Hollywood jazz composer Billy Allen. This image reflects the collaborative, regional nature of the production.

Making The Devil’s Mistress

The Devil’s Mistress was Wanzer’s first film. Shot over several years on weekends, it was made with a single 16mm Bolex, limited film stock, and a small local crew. Wanzer formed WGW Productions (Wesmoreland, Gregory, Wanzer), whose members also served as cast and crew.

Working on a low budget, the crew rarely reshot scenes. To conserve film stock, they relied on careful planning, rehearsal, and precision before the camera rolled. By his account, the budget hovered around $20,000—modest even by mid-1960s standards. Rather than “fast and cheap,” the film emerged from patience and constraint, merging European art-cinema deliberateness with the visceral charge of American exploitation flims.

Desert Drift. Screen still from RGHC 0055 loose reels.

Liah, Freddie, and Will traverse the foothills on horseback. Movement here is directionless and cyclical, emphasizing drift over destination. The landscape absorbs the characters, flattening hierarchy and narrative urgency.

A Psychological Landscape

Filmed entirely in the Organ Mountains and the Mesilla Valley, The Devil’s Mistress treats the desert as a psychological mind-space rather than a backdrop alone. Characters move without clear purpose, driven by fear, necessity, and happenstance instead of narrative logic.

This drift recalls what Situationist theorist Guy Debord called dérive—movement shaped by affect and unconscious association rather than intention. But where the urban dérive embraced play, experimentation, and deliberate openness to chance, Wanzer’s desert drift is led by unwanted disturbances, callous misdirection, and unreliable circumstances. Over the course of a few nights, the group roams the foothills in cyclical patterns, overwhelmed by a landscape that erodes agency rather than inviting exploration.

Here, drift signals not possibility but breakdown. Meaning loosens, control collapses, and the environment asserts itself as an indifferent force. In this way, The Devil’s Mistress anticipates the Acid Western’s psychological terrain: a landscape of disintegration, where surrealism no longer generates new situations but exposes the characters’ loss of footing within a hostile world.

Paranoia and Recognition.

Screen still from RGHC-0055.

Will observes Liah from a distance, gripped by doubt. The camera lingers as guilt, fear, and foresight converge—knowledge arriving too late to alter its consequences.

Realism, Time, and Restraint

“Realism in art can only be achieved in one way—through artifice.”

Wanzer’s realism draws from European cinema’s attention to duration, presence, and ambiguity. Like Italian neorealism, the film favors real locations, non-professional performers, and respect for time unfolding without narrative reassurance.

Scenes surrounding the murder of Jeroboam and the capture of Liah unfold in real time, producing a slow, unsettling lack of propulsion uncommon in the Western. Long takes linger beyond comfort; interactions unfold without predictable cause or moral framing. Meaning is deferred rather than resolved. Characters are frequently framed in long shots, dwarfed by an imposing, indifferent landscape.

Wanzer combines Hitchcock’s formal control with the abrasive sensibility of American exploitation and the contemplative pacing of European art cinema, allowing reality to emerge within the story rather than be imposed upon it.

Jereboam reappears… Screen still from RGHC-0055.

Jeroboam reappears transformed—shaved, costumed, and framed as spectacle rather than threat. The red-lined cape, exaggerated reveal, and ritualized posture foreground artifice, marking a deliberate turn toward excess. Wanzer’s refusal of restraint at the film’s end asserts cinema’s power to stage meaning through stylization alongside realism.

Camp, Experiment, and Film as Art

In press materials and public statements from this period, Wanzer repeatedly argued that cinema was becoming a fine art—an idea still far from consensus in the early 1960s. At New Mexico State University, he programmed foreign films, silent-era cinema, and early surrealist works through the Campus Film Society he co-founded in 1959. Alongside his Film as Art courses, Wanzer introduced students and local audiences to cinematic traditions that treated film as a serious aesthetic and philosophical medium.

This experimental foundation surfaces most clearly in The Devil’s Mistress through moments of excess, stylization, and tonal instability that verge on camp. Ritual gestures, heightened performance, and symbolic costuming operate in a register that is at once sincere and knowingly excessive. The Devil’s return—marked by the red-lined cape, the exaggerated reveal, and the collapse of restraint into spectacle—functions not as parody but as an embrace of artifice. It announces cinema’s power to stage meaning rather than merely represent it.

Here, camp becomes a mode of critical excess: a way of pushing realism until it breaks open into something stranger, theatrical, and unstable. While the film does not foreground queer identity as explicit subject, its embrace of performativity, erotic ambiguity, and the fragility of masculine authority places it in dialogue with underground and experimental cinemas emerging at the margins of the period—spaces where art, identity, and desire could be tested precisely because they were not yet stabilized.

“What rough beast…”

Screen still from RGHC-0055.

After subduing the final outlaw—who had professed affection for her—Liah tears out his heart with a knife. The act initiates Jeroboam’s return and collapses distinctions between victim and predator, punishment and prophecy.

Athaliah (Liah): Power Without Rescue

At the center of the film stands Liah—Wanzer’s Old Testament–inspired Bruja in the original script—who becomes The Devil’s Mistress upon theatrical distribution. Neither victim nor moral anchor, her agency oscillates between constraint and unleashed force, prophecy and punishment.

Her encounters with the cowboy outlaws expose masculinity not as strength, but as performance: brittle, cruel, and unstable. Justice, when it appears at all, is partial and unsettling. Liah’s revenge—ravenous and bestial even as she remains inward and contained—is activated through erotic encounter and ritual violence, sealing the men’s fates along with their final chance at redemption.

First Blood

Screen still from RGHC-0055.

The morning after Liah’s abduction, her first victim falls dead from his horse. Violence arrives suddenly, without moral framing, initiating the cycle of retribution and return that governs the remainder of the film.

Borderlands, Absence, and Haunting

Although The Devil’s Mistress does not directly depict the historical violence involving Mescalero Apaches, Mexican forces, and U.S. military power, those histories remain present as structuring absences. The cowboys’ fear of the Apache and fantasies of escape into Mexico reveal a masculinity haunted by violence it refuses to confront directly.

This haunting takes visual form in moments like the morning after Liah’s abduction, when one of the cowboys is found dead, collapsed from his horse. The men gather around the body in confusion and dread, unable to name the cause of death or its meaning. In the background, Liah approaches—almost faceless, nun-like, spectral—watching silently as they stare downward. Her presence is barely acknowledged, yet unmistakable.

Violence here arrives not as moral reckoning or narrative justice, but as intrusion. The desert becomes a purgatorial space where history returns sideways—through paranoia, repetition, and fear rather than memory. Liah’s gaze, unreadable and withheld, marks the beginning of a cycle in which punishment unfolds without explanation, and guilt circulates without resolution.

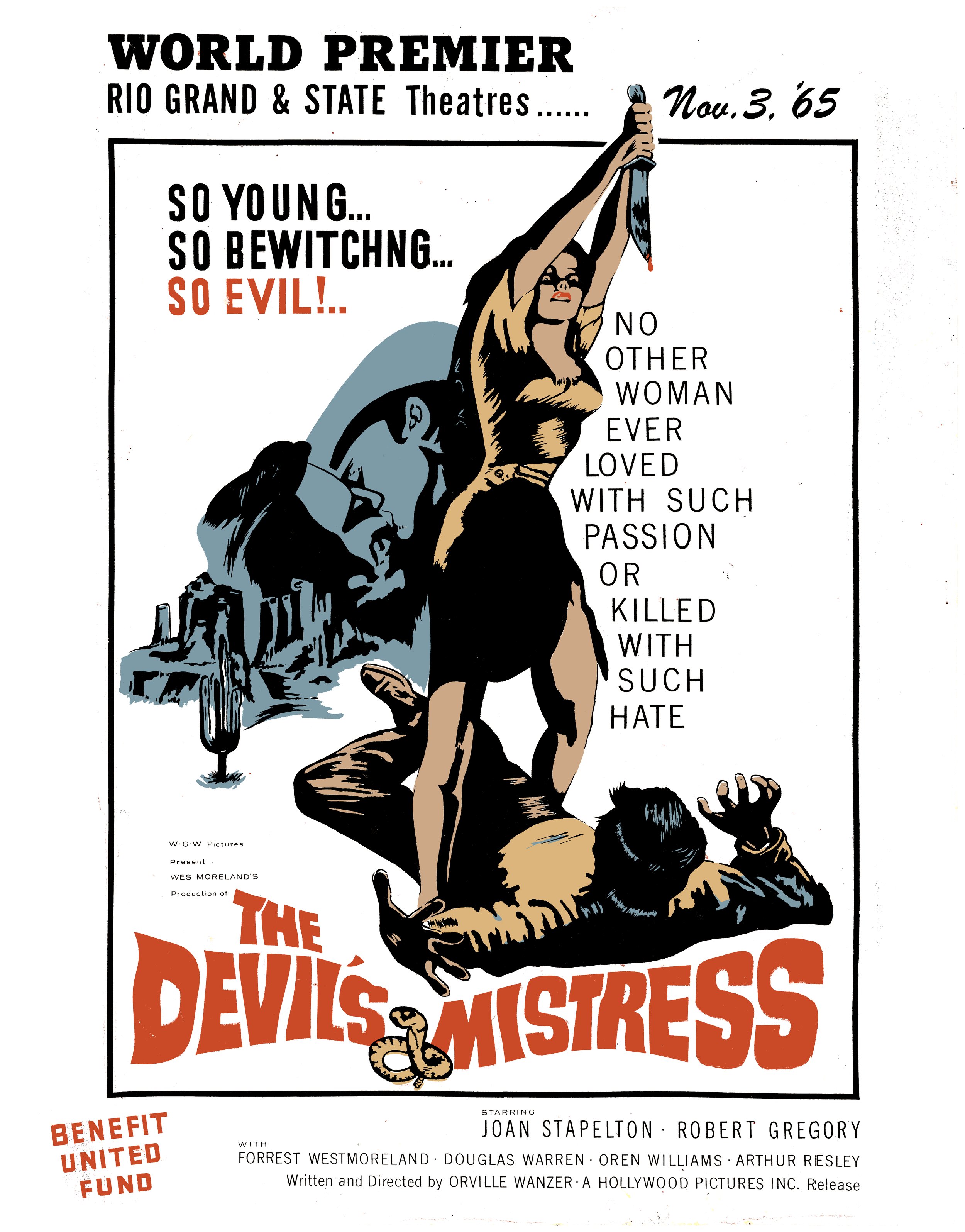

World premiere poster.

Original poster for The Devil’s Mistress, courtesy of Teddy Gregory.

Digitally enhanced to reflect the original print.

Promotional materials emphasized shock, sexuality, and gothic menace—signaling the film’s uneasy position between art cinema and exploitation.

Precursor to the Acid Western

Viewed retrospectively, The Devil’s Mistress reveals tensions later associated with the Acid Western: drift over conquest, breakdown over progress, ambiguity over moral clarity. Long before the genre entered critical discourse, Wanzer fused realism and excess, patience and provocation, art cinema and exploitation.

Like later Acid Westerns, The Devil’s Mistress transforms drift from an experimental openness into a condition of entrapment, where characters lose control not by choice, but by being overtaken by their environment, its history, and their own unraveling masculinity.This was not Hollywood’s West—it was a regional, unstable one, shaped by geography, history, and disillusionment.

Ritual reversal.

Screen still from RGHC-0055.

Liah kneels in the foreground, knife raised above her head as she prepares to remove Frank’s heart. This moment echoes the film’s opening conversation, in which the cowboys fantasize about finding a Native woman, assaulting her, and gutting her. The fantasy returns as ritual action—reversed, embodied, and fulfilled.

Emerging from southern New Mexico—shaped by agriculture, militarization, and border circulation with El Paso and Juárez—The Devil’s Mistress exemplifies a harsher, more fatalistic Western tradition with diminished faith in redemption.

The film is not a footnote. It is a precursor. Its rediscovery complicates American film history and reminds us that genres often begin long before they are named.

Closing

Part of the ongoing archival and documentary project Birth of the Acid Western.